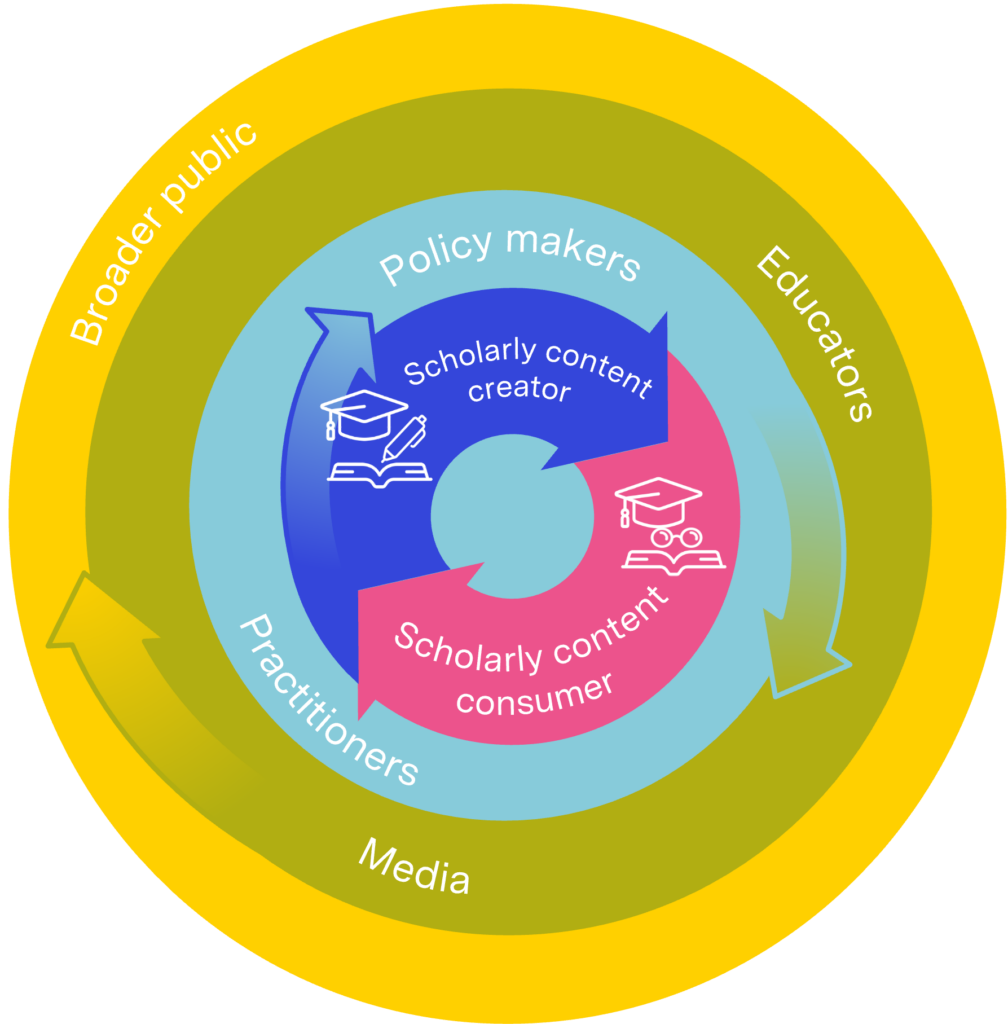

The traditional role of scholarly publishers has been the communication of research within academia -- for example, making sure scientists find out about others' discoveries, to aid scientific progress. From the moment I joined the scholarly sector, almost 25 years ago, the received wisdom was that "this is an unusual market, because it is circular: the content creators are also the content consumers". Over the last 10 years or so, I've been working to disprove that. There is a broader audience for research, and it's a really important one. Research publications have the power to change the world; they contain the answers to some of the world's most pressing challenges. But to do that, they must escape the 'circle', and be found, read, understood and acted on by more people.

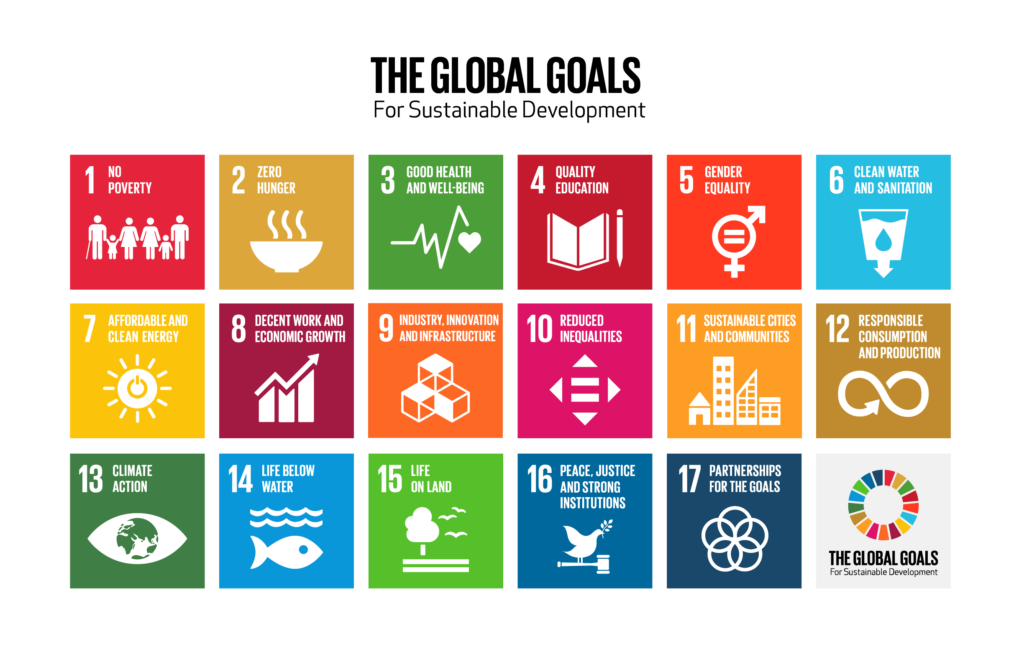

I've got even more tub-thumpingly passionate about this in the last couple of years, since I started curating thematic research showcases that address global challenges such as climate change or the SDGs. Through these projects I have been diving deeply into research undertaken in these areas, to find those articles that are not just loosely relevant to these topics, but that really do contain the answers. For those who aren't yet aware, the SDGs are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, a set of targets that UN members have signed up to achieve by 2030. They are structured into 17 themes ranging from poverty and health, to sustainable consumption, peace and justice. An important and little known aspect of the SDGs is that we are all on the hook to help achieve them. They replace the earlier Millennium Development Goals, and correct for the fact that those earlier goals made less developed countries responsible for solving problems that in many cases had been caused by more developed countries. The SDGs address that and allocate much greater responsibility to developed countries, though many of their citizens are alarmingly unaware of what they have been signed up to.

Challenge 1: identifying relevant content – and not overstating

In the scholarly publishing sector, a lot of activities are underway to try and support progress around the SDGs, including the SDG Publishers Compact, whose fellows (disclosure: I am one) have created a set of 'top tips' for aligning practices and content with the goals. The STM Association's SDG Roadmap also provides publishers with step-by-step guidance for translating the goals into organizational change. Many organizations are working to try and categorize published research against the SDGs, but this is another area where I can get a bit tub thumpy as it's too easy to overstate the relevance of publications to the goals, and doing so is dangerously counter productive. The well-known branding of the high level goals possibly exacerbates this because people think anything to do with any of these 17 headline topics can be counted as relevant to the SDGs. But in fact, the SDGs are much smarter than these broad goals. They are literally SMART -- each goal breaks down into around 10 smart objectives, targets, and indicators. So for example, goal 7 (clean energy) is being measured by metrics such as the proportion of the world's population with access to electricity while indicators for goal 11 (sustainable infrastructure) include the proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing. This is really specific stuff and the reason I think it's dangerous to overstate the quantity of relevant content we publish is that it overwhelms us, and prevents us from taking some of the quick actions that would really help. Achieving these goals / moving the needles on these indicators is heavily reliant on getting this research OUT of the academic sphere and IN to the broader audiences whose actions, behaviors, circumstances, etc. are measured by those indicators. If we think we've got to do that job for 75% of the content we publish (some organizations have suggested that is the proportion of scholarly content that is relevant to the SDGs), we are daunted by the scale of that task. If we realize that, actually, most publishers have perhaps 20 to 50 articles per year that are properly relevant to the goals, the idea of making sure that content is found, read, understood, and acted on by relevant audiences becomes much more manageable.

This is really specific stuff and the reason I think it's dangerous to overstate the quantity of relevant content we publish is that it overwhelms us, and prevents us from taking some of the quick actions that would really help. Achieving these goals / moving the needles on these indicators is heavily reliant on getting this research OUT of the academic sphere and IN to the broader audiences whose actions, behaviors, circumstances, etc. are measured by those indicators. If we think we've got to do that job for 75% of the content we publish (some organizations have suggested that is the proportion of scholarly content that is relevant to the SDGs), we are daunted by the scale of that task. If we realize that, actually, most publishers have perhaps 20 to 50 articles per year that are properly relevant to the goals, the idea of making sure that content is found, read, understood, and acted on by relevant audiences becomes much more manageable.

The indicators (as opposed to the top level goals) give us the focus we need. For example, it's not a case of thinking 'how are we going to get all our health and well-being content in front of broader audiences?'. It's a case of looking at 'what content do we have that could help reduce maternal mortality ratios (MMR)?' (indicator 3.1.1) and looking for very specific case studies and recommended interventions, for which wider promotion could substantially increase implementation and impact of the findings. When you take that approach, you find answers, such as this article in BMJ Open Quality in which a group of five hospitals in Saudi Arabia worked together to make childbirth safer, and were able to reduce MMR in the country from 10.5 per 100,000 births in 2018 to 4.6 per 100,000 births in 2020. Or how about asking what content we have that would underpin improvements in the proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services (indicator 6.1.1) -- this article in Sage's Race and Justice journal looks like it will have some useful recommendations.

Challenge 2: what research we value vs what research actually changes lives

One of the issues that comes to the fore as we try and solve the SDGs is the question of how we value research. As I've explored this topic it's become increasingly clear to me that a lot of the most relevant research falls outside of what would traditionally have been considered "high impact", "significant", etc. For example, the SDGs are aiming to improve quality of life (etc.) for people in disadvantaged communities -- people who are poor, people living in desert regions, people being abused, exploited, or trafficked, and so on. Crudely put, these are not fashionable areas for research funding or publications. The issues here cross over all the fault lines in our sector: the lack of respect for localized research studies (not big enough to warrant attention); the snobbery / mistrust in relation to research led by organizations outside of the traditional research-intensive countries (not invented here / don't know the names involved); the institutional career advancement frameworks that push for publication in international journals (and thereby discourage write-up of small / local studies that won't meet the criteria for those journals) -- etc.

So often in my work to identify, summarize, and publicize studies that really address the SDGs, they are small scale, local studies. The techniques developed by ranchers in California to cope with drought could be implemented by farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. But making sure piece-of-research-A gets in front of relevant-audience-Y hasn't been part of the traditional remit of scholarly publishers. I think that is changing; I do see organizations beginning to reorient around the triple bottom line (i.e., focusing as much on social and environmental concerns as they do on profits) and beginning to think creatively about the role they can play here. Hat tip to Canadian Science Publishing, for example, for the work they are doing to support, guide and publicize indigenous research.

Challenge 3: even the most basic research needs to be communicated more broadly

I frequently get told by publishers that they publish basic research and there is no broader audience for basic research. I get really tub thumpy when told this, for two reasons: one is that all basic research has exciting potential, and especially when it comes to things like climate change, people in the 'broader audiences' (aka 'the real world') really need the HOPE that is offered by basic research. We need to know it's not too late and that science is going to save us. (It is. The Royal Society of Chemistry, for example, has published many fascinating articles that give me hope e.g., how carbon-nanomaterials are going to make rice production less environmentally damaging, or how a new material will lead to less carbon dioxide being released during the production of useful chemicals such as ethylene).

The other reason was articulated well by Deborah Blum during her keynote at this year's Society for Scholarly Publishing Annual Meeting ("Publishers in the Age of Mistrust"). We need to lift the lid on basic science as much as any other kind of science, because faith in science is on the wane and we need to step up to the challenge of communicating to people "beyond re-educating the choir" (Blum's words). We have to be creative in how we communicate research to people who don’t want to engage with science. Research publications make people feel stupid and no one likes feeling stupid. “There are ways to get information out there that are not a lecture,” said Blum in her closing point. For me, that means telling stories around the science, mapping it to news stories or awareness days or other interesting developments, sharing and showcasing, and firmly banging the drum. Even if you think you publish the most basic of basic science and no-one except scientists could possibly be interested in it, or understand it, or benefit from it: think again, because you are part of the circle of trust. If we are going to tackle the extraordinary challenges facing humankind today, we need to influence the behaviors and attitudes of an extraordinary wide range of people. And we need to start by convincing those people that science is working in their interests; that science will help to solve these problems. If the basic science you publish underpins applied science down the line, people need to know that now.

In conclusion, then, the role of scholarly publishers is evolving – has evolved? – from a closed loop of content creation and consumption within academia to a broader mission of communicating research to broader audiences. By breaking out of our traditional sphere, we can ensure that research addressing global challenges like climate change and the SDGs reaches those who can implement and benefit from these findings. This requires not only a purposeful approach to identifying and explaining relevant content, but also rethinking what research we value. The content we publish has the answers; our job is to ensure they are heard and acted upon.

This post was originally published in today's Scholarly Kitchen.