Every drop of funding now seems to come with requirements around achieving and demonstrating broader impacts. Not many of us disagree with that in principle, but what does it mean in practice? How is impact actually achieved? How can you measure it? What can you actually do to accelerate it? Here’s what our co-founder Charlie Rapple had to say in a recent webinar.

This post is 10 minute read. Here is your 1 minute summary:

- Research impact is real change in the real world.

- There are many different kinds of impact including attitudinal, awareness, economic, social, policy, cultural and health.

- It takes hard work and persistence to create impact from research.

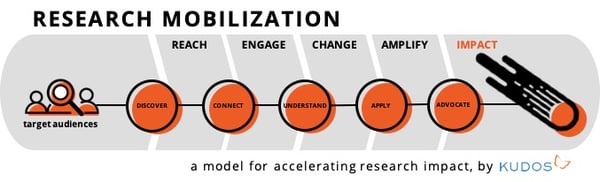

- Impact is achieved through several steps that include helping relevant audiences to discover, connect with, understand, apply and advocate for research.

- Impact is best achieved through stakeholder engagement throughout the lifecycle of a project.

- National assessment programmes and funding agencies are placing increased emphasis on dissemination and impact evaluation, particularly outside of academia.

- Evidencing and measuring impact are controversial and fast developing areas – likely to comprise a mix of quantitative indicators and qualitative reviews.

- Researchers will need to develop new skills and capabilities to demonstrate ability to create impact, which could become central to career progression and institutional reputation.

- Find out more about our new platform to help you plan and manage communications to maximize the impact potential of your research.

1. What is research impact?

You will find several definitions of impact from funders and universities, for example:

You will find several definitions of impact from funders and universities, for example:

- US National Institutes of Health: The likelihood for the project to exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved.

- Research England: An effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life beyond academia.

- US National Science Foundation: The potential [for your research] to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of desired society outcomes.

- Australian Research Council: The contribution that research makes to the economy, society, environment or culture, beyond the contribution to academic research.

While there are some subtle differences, they broadly agree that “impact” means demonstrable and beneficial change in behaviours, beliefs and practices. At Kudos, we like the simplicity of this definition from Julie Bayley, Director of Research Impact at the University of Lincoln:

“Provable change [benefit] of research in the ‘real world’.”

The real world part is key. Traditionally, assessment of impact has focused too much on academic impact – whereas, in reality, impact is measured by indicators of change outside universities and research institutions, in the real world.

Having defined impact at this high level, it’s then possible to define a number of types of impact. Professor Mark Reed, Director of Engagement & Impact at Newcastle University, has analyzed impact case studies from around the world, and proposes ten types of impact:

- Understanding and awareness – meaning your research helped people understand an issue better than they had before

- Attitudinal – your research helped lead to a change in attitudes

- Economic – your research contributed to cost savings, or costs avoided; or increases in revenue, profits or funding

- Environmental – benefits arising from your research aid genetic diversity, habitat conservation and ecosystems

- Health and well-being – your research led to better outcomes for individuals or groups

- Policy – your research contributed to new or amended guidelines or laws

- Other forms of decision-making and behavioural impacts

- Cultural – changes in prevailing values, attitudes and beliefs

- Other social impacts –such as access to education or improvement in human rights

- Capacity or preparedness – research that helps individuals and groups better cope with changes that might otherwise have a negative impact.

Professor Reed’s book, The Research Impact Handbook, is highly recommended – even required reading – if you’d like to learn more about each of these areas, and how to understand the potential outcomes of your research in each area.

2. Why does impact matter?

Impact is important because it helps keep us focused on the overall purpose, rather than the process, of research. Some of the legacy ways in which research is undertaken, communicated and evaluated have put up barriers between the work itself and those who may benefit from it. If we reduce the barriers between those producing research and those that can apply it to make change in the real world, we will be in a much better position to take on the grand challenges faced by the world today.

Impact is important because it helps keep us focused on the overall purpose, rather than the process, of research. Some of the legacy ways in which research is undertaken, communicated and evaluated have put up barriers between the work itself and those who may benefit from it. If we reduce the barriers between those producing research and those that can apply it to make change in the real world, we will be in a much better position to take on the grand challenges faced by the world today.

A focus on impact, then, helps us ensure the best possible return from the investments that we – as a society– are making in research.

At a more everyday level, research impact matters to individual researchers because it matters to funders! The organizations that control research funding are under pressure to audit and evaluate their spending. For example, government policy makers want to know that they can rely on government-funded research to be high quality and highly relevant. Charitable funders need to be able to show donors how outcomes are being improved as a result of their donations. Institutions such as universities want to prove that they are the best, to attract more students, more researchers and more donations.

3. How is impact achieved?

Because of the role that past and potential impact plays in funding decisions, this is literally a billion dollar question. There is no single, simple answer. But the question of what kinds of steps help to achieve impact has been widely considered.

- Reach: communication of knowledge is key to impact. You need to reach the audiences that can best build on or benefit from your work.

Why? Your findings will not be able to deliver any kind of change if no-one knows about them. - Engage: you need to interact with those audiences – whether they are policy makers, industry, educators, healthcare practitioners, the media, or the public – to understand their needs and existing level of expertise, and to be able to address their feedback as your work evolves.

Why? Your findings will not be able to deliver any kind of change if they are not relevant to potential stakeholders or beneficiaries, or if they cannot understand them. - Change: you need to be thinking from early in the research process about the kind of change you want to create – whether that is changing behaviours, attitudes, awareness, processes, policy, product specifications (see Mark Reed’s ten types of impact, above).

Why? As above – impact must be more than an academic concept for it to be truly valued by the real world, and thus by research funders and institutions. - Amplify: you need to think about how any change you can bring about will scale such that its effect is as significant, widespread and lasting as possible. For example, how can a benefit to the local community be translated to national or even international impact?

Why? To maximize the impact potential of your work, and the return on the investment that you and your institution or funder have made.

An important point to remember in this context is that routes to impact are not, in themselves, impact. Running a workshop, producing a report, meeting a company are all activities that can help you progress through this process. But in themselves they don’t represent provable change in the real world. It may be easier to track and measure those pathways than it is to identify the downstream outcomes that result from them.

This is one of the problems we’re working on at Kudos, helping researchers to capture the breadcrumb trail to link impact back to these activities. You can read more about our platform for this here.

4. How is impact measured?

Many researchers today are incentivized by their institutions to prioritize publication over impact. Until those incentive systems change, making time to develop and demonstrate impact can be hard to justify. However, things are changing, and fast! Mark Taylor, Head of Impact at the National Institute for Health Research, says that there are four broad reasons for measuring impact:

Many researchers today are incentivized by their institutions to prioritize publication over impact. Until those incentive systems change, making time to develop and demonstrate impact can be hard to justify. However, things are changing, and fast! Mark Taylor, Head of Impact at the National Institute for Health Research, says that there are four broad reasons for measuring impact:

- Advocacy – helping gain support from the public, funders, government etc

- Accountability – showing what you are achieving with your work

- Analysis – finding out which approaches to research are most effective

- Allocation – considering where it is most appropriate to invest research funding.

Measuring impact is notoriously difficult (hence many funders and systems still resort to using publication-based proxies such as the Impact Factor or citation counts – which really reflect routes to impact rather than impact themselves, and even then, only within academic audiences). A more nuanced way of assessing impact is through narrative-based case studies, or by looking at tangible outcomes – impact evidence – that can be recorded and reported on via impact trackers or impact modules within university systems. Trish Greenhalgh writes and speaks eloquently on this subject. In her view, there is a trade-off between breadth and depth. If you want to measure the impact of every bit of research that everyone in a university has ever done, you have to use something that is easy to measure and probably automated. But if it is more important to get a rich and authentic picture of a sample of research programmes, this needs to be looked at in a lot more detail – balancing measures with narrative. The Metric Tide report (produced by the Higher Education Funding Council in the UK) also concluded that quantitative measures can’t yet replace qualitative assessments of quality and impact.

There is a lot more work to be done here! What is perhaps more measurable are the various steps from access to impact that we explored above; efforts to maximize reach, engage audiences, achieve and amplify change are all increasingly measurable. Over time, as those measures can be linked with ultimate outcomes, we will learn more about not only how to measure impact, but what to do to achieve it, too.

Charlie Rapple is one of the founders of Kudos, which has recently launched a new platform to help plan and manage communications to maximize impact potential of research. Charlie previously spent 20 years as a marketing and communications specialist in the academic sector, helping publishers and universities to communicate research.